By Sharon McInnes

When I first read Alison’s Fishing Birds, just published by Caitlin Press, my impulse was to co-opt children from the playground, gather them around, and read them the stories. But I didn’t, hoping instead that you will read these lovely stories to the children in your lives.

Roderick Haig-Brown is believed to have written Alison’s Fishing Birds in 1939 or 1940 but the stories were only discovered after his death in 1976. One of BC’s most influential conservationists, he emigrated to British Columbia from England as a young man, eventually settling near Campbell River and becoming its magistrate for over thirty years (http://www.haig-brown.bc.ca/.) There, on the east coast of Vancouver Island, Haig-Brown was captivated by the natural world and became active in the Nature Conservancy of Canada, the BC Wildlife Federation, and several fly-fishing organizations. Lucky for us, he also wrote twenty-eight books celebrating the natural world including Starbuck Valley, The Whale People, and this gem, Alison’s Fishing Birds.

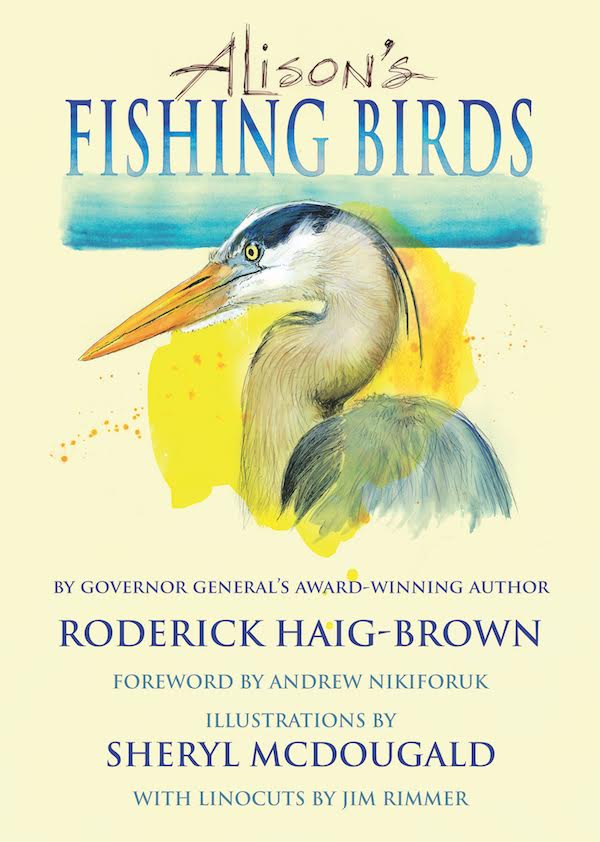

What I like most about the connected stories that make up Alison’s Fishing Birds, beautifully illustrated by Sheryl McDougald and Jim Rimmer, is their capacity to create deep empathy for the natural world. It’s hard not to identify with Alison’s surprise and delight when the dipper suddenly lands on a rock “not more than half a dozen steps away from her” or when her father leads her to the kingfisher’s nest with eleven eggs “all neatly packed together in a hollow among the roots”.

And it’s just as hard not to identify with her concern when the eagle snatches the fish from the osprey who’s worked so hard to catch it or when the Belted kingfisher eats so many fish she’s worried he won’t be able to fly. The birds, of course, set her straight, every time. Alison accepts their lessons gratefully and gracefully, keen on knowing “what the birds are really like and what they really do.” Who can fail to admire that?

Haig-Brown’s Alison is a “quick little girl” who learns about the ‘fishing birds’ by the river – dipper, kingfisher, heron, merganser, and osprey – with her father’s thoughtful guidance.

But mostly she learns through mindful observation, whether from the window of her family’s brown house with the pale blue trim, or hiding in the “secret place she had near the pasture fence”, or walking along the river bank. Alison knows how to pay close attention, resisting the urge, for example, to scratch her nose or pull her dress “down a little on her shoulder, where it was uncomfortable” to avoid scaring off Walk-up-the-Creek, a fine old heron fishing by the river.

In his title story Haig-Brown assures us that “You couldn’t call Alison a naturalist or bird watcher or anything dull like that. She didn’t sneak and peer and creep around looking for birds, but she liked to go up the river and she was quiet and her eyes were quick …”

Maybe Alison doesn’t “watch” birds, but she does observe them closely and studies their habits and behaviour, and even talks to them – and sometimes they talk back, teaching her important lessons about their particular niche in the natural world. They make her think and wonder and worry and hope and give her stories to tell her dolls at bedtime.

In the foreword environmental writer Andrew Nikiforuk says of Haig-Brown’s (and Alison’s) penchant for watching the natural world: “Any engagement with wildlife – whether listening to the chatter of river otters, hunting grouse or watching a black bear denude an apple tree – restored human meaning and brought us back to the point of things: there is no end to wonder and joy when you care about a place.”

Indeed, these stories offer readers the opportunity to share in the wonder and joy of a few of the ‘fishing birds’ that live here on the far west coast. And McDougald’s detailed illustrations of not just the birds but also elements of their habitat – bumble bee, Pacific tree frog, coastal gum plant, western red-backed salamander, dragonfly, clam shell, and various types of feathers – add immensely to the reality of the sense of place.

I’m confident that parents, grandparents, teachers, and anyone else with young children in their lives will find this a perfect book to read with them or to them. I must admit, I’ve already read it several times, all by myself, for the sheer pleasure of the stories and illustrations.

One more thing – a word of advice to readers who typically ignore the preface of a book: don’t ignore this one. Valerie Haig-Brown’s story of how Alison’s Fishing Birds came to be published, decades after the death of her father, is a heartwarming tale all on its own.

Thank you to Caitlin Press, who sent me a copy, no strings attached!

Sheryl – You’re welcome! It was a pleasure for me too.

Thanks Marianne!

We totally agree. Wonderful book for parents and grand parents to read to the the children in their lives. I am also passing copies aling to bird watchers I know!!

Thank you, Sharon, for the thoughtful, delightful review!! It was a Dream Project for me!